Dynamic Landfill Management

What is DLM?

Since 2019, Dynamic Landfill Management has been the all-encompassing term for the sustainable integration of resources (materials, energy and land) from landfill sites into the circular economy. This includes the safe storage of landfills with a high resource valorisation potential, in view of enhanced landfill mining (ELFM), providing sustainable interim uses and bridging the gap to a final safe situation and thereby respecting the most stringent social and ecological criteria.

The objective of Dynamic Landfill Management is to bring landfills into harmony with their dynamic environment. On the one hand, this includes preventing or reducing negative effects like environmental and health-related risks as far as possible. On the other hand, DLM tries to maximise positive effects, so that old landfill sites can contribute to national as well as European policy goals in the broadest sense, e.g. concerning waste and resource management, climate change, the Blue Deal, the Green Deal, soil sealing and no net land take.

Downloads

The Enhanced Landfill Mining (ELFM) option

Currently, there is a rising worldwide demand for raw materials and energy sources. Keeping materials in the cycle or even reusing materials that were temporarily absent from the materials cycle is therefore a major challenge to entrepreneurs, consumers and policy-makers.

Landfill sites can be a potential new source of materials or energy. With this as a goal, they can be exploited through Enhanced Landfill Mining (ELFM). The ELFM concept aims at an R³P goal: Recycling materials, Recovering energy, Reclaiming land and Preserving drinking water supplies. ELFM is a concept in which materials and energy from landfill sites are valorised as sustainably as possible by maximising materials recycling and optimal energy production. It is thus the most ideal option within the Dynamic Landfill Management strategy.

From ELFM to DLM

While it is a possibility, current economic conditions do not favour this option for the vast majority of landfills. Exceptions are mono landfills, where the deposition of a single waste stream reduces the need to separate it from other materials. This does not negate the fact that landfill mining may one day be preferential to other methods of acquiring specific raw materials. In the current economic climate, however, there are 2 key drivers for performing excavation:

- reducing risks of pollution due to deterioration of the landfill’s containment measures/external factors or;

- supporting redevelopment of the area.

When applying DLM, it is important to set up a management strategy that is not only based on the content of the landfill (landfill characteristics). The context of the landfill should also be taken into account in the decision-making process (e.g. surrounding environment, market conditions, predicted environmental change). There is therefore no ‘standard’ for applying DLM. Aside from the technical requirements for the design of a landfill, DLM must take into consideration the legislative context (such as the soil decree), the impacts of external factors like the increasing effects from climate change, as well as better data infrastructure for sharing information on existing landfills and implemented projects. Moving forward, all these aspects should be considered in future policy and the development of legislation concerning landfills.

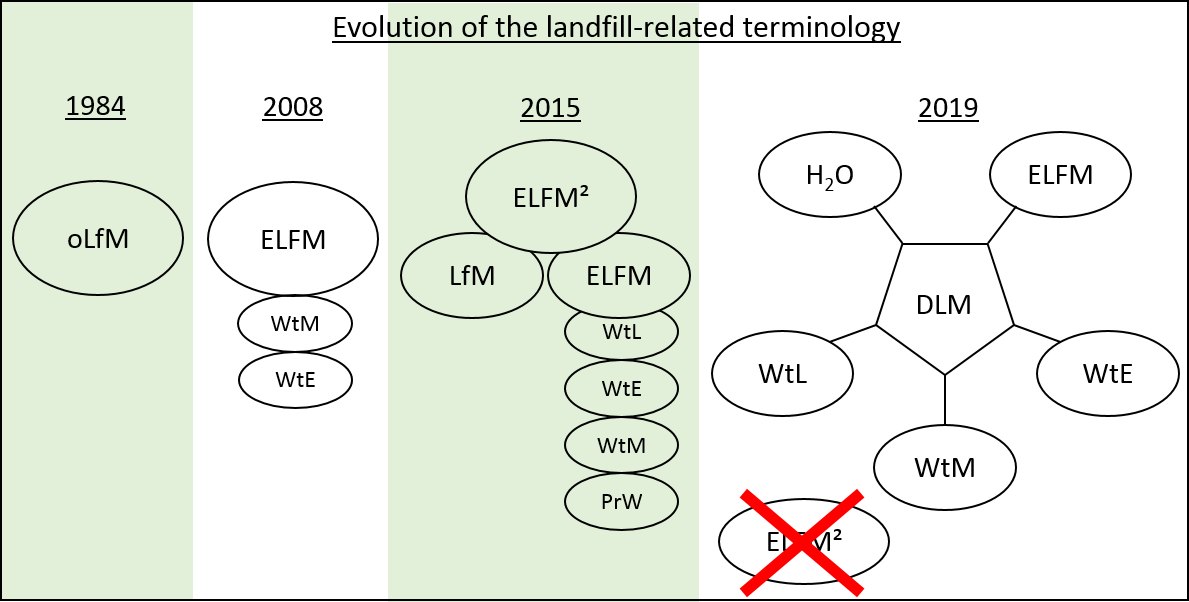

Development of terminology around landfill management. Operational Landfill Management (oLfM); Enhanced Landfill Mining (ELFM); Enhanced Landfill Mining & Management (ELFM²); Landfill Mining (LFM); Landfill Management (LfM); Waste to Materials (WtM); Waste to Energy (WtE); Waste to Land (WtL); Prevention of Groundwater (PrW).

Why DLM?

The OVAM database contains about 3,300 landfill sites in Flanders. The total space taken up by these sites is larger than a medium-sized city. It is estimated that there are about half a million comparable sites scattered across the European Union.

Most of these landfills originated between 1945 and 1995, in particular during the development of the consumption society. The effects of half a century of dumping activities have only been considered problematic since the 1980s and involve the pollution of the environment and the obstruction of zoning options. Sustainable management of these sites is important in a densely populated region like Flanders, where landfill sites in and around built-up areas could make an important difference to the quality of life.

Furthermore, Flanders has expressed the ambition to take important steps towards a circular economy, thereby minimising the use of raw materials, energy, water, materials and space, with as little impact as possible on the environment and nature in Flanders and the rest of the world.

Bringing theory into practice

At European level

OVAM has participated in several European Interreg projects on ELFM and DLM - COCOON, RAWFILL and REGENERATIS. While COCOON focused on policy changes to facilitate the implementation of (dynamic) landfill management, RAWFILL developed a comprehensive methodology to support new business models that address resource recovery and the rehabilitation potential of landfills. This methodology is data-based, including an inventory framework, decision-support tools and innovative landfill characterisation using geophysical investigations. The REGENERATIS project focuses on the regeneration of Past Metallurgical Sites and Deposits (PMSD).

In Flanders

Meanwhile, OVAM has been actively incorporating the lessons learned from these European projects, into its own working and policy domain. To support and facilitate Dynamic Landfill Management in Flanders, OVAM implemented a three-step strategy:

- Mapping: building a landfill inventory

- Identifying/surveying: description of landfill characteristics

- Exploration/data mining/valorisation: exploring options for different DLM scenarios

The first step in managing Flanders’ landfills is determining how large the stock is and where the different landfills are situated. The various OVAM databases are the ideal starting point for this process. The information that is stored in the Land Information Register (a register with all relevant information about land plots and soil contamination) was matched with the tax database for licensed landfill sites and the so-called POT archive. The POT archive is an inventory of plots of land on which activities took place that potentially contaminated the soil, and includes landfill sites.

Between 2012 and 2013, OVAM took the first steps in building up a landfill inventory for Flanders. In this first version of the dataset, about 2000 landfills were included. The second step (identifying/surveying) focused on content-related data, to determine the potential of these landfills for Enhanced Landfill Mining. A methodology was then developed to prioritise landfill sites, both by their need for remediation and by ELFM potential. This decision-supporting model has been applied to a test series of 72 landfill sites. In 2013, the model was further refined and documented as Flaminco (Flanders Landfill Mining Challenges and Opportunities).

Over the years, the Flaminco database has been updated as new sources of landfill information were obtained, e.g. data from municipal inventories. By 2020, 3318 landfills had been included in the landfill database.

The data structure was changed around 2018, based on new insights derived from European projects and the focus shift from ELFM to DLM. The new inventory format was based on the structure of the Decision Support Tool, Cedalion, which was developed in the RAWFILL project. The landfill inventory is therefore called Cedalion. At this point, context-related data was added to the dataset, in view of the rehabilitation potential of the landfills and the potential for certain DLM strategies. To achieve this, OVAM consulted the experience and knowledge of VITO. General and location-specific characteristics of landfill sites were looked at in terms of land use. Indicators were drawn up that reflect the spatial condition of, and dynamics in the environment and thereby also quantify the spatial pressure exerted on the sites.

Eventually, OVAM managed to create a landfill inventory that includes information related to both the content and context of the landfill. This database enables exploration of the different options for these landfills, in terms of valorisation potential and redevelopment. This allows the best DLM strategy to be chosen, as a function of the specific characteristics of a certain landfill. However, it is also possible to work the other way around. Starting from a certain policy goal (e.g. the Blue Deal, Green Deal, the need for residential areas), different landfills can be selected as a function of pre-defined criteria.

In 2021, OVAM set up an afforestation project to support the policy goal of the Minister of Environmental Affairs to achieve 4,000 ha of additional forest by 2024. In this case, the landfill database was used to explore the options for afforestation, thereby identifying the high-potential areas. In a first phase, municipalities with a landfill in their area could sign up to the project and, if they ensured afforestation, OVAM would do a preliminary soil investigation at its own expense. During such investigation, landfill will be screened against its afforestation potential, based on the characteristics of the landfill and the waste present.

It is, however, important to note that afforestation may not always be the best option for a particular landfill. If the local environment has no need for a forest, another DLM strategy should be considered.